Western Piedmont - History Project

The Fight for Equality

Early African American Schools

Lost Community - Fonta Flora

An Oral History of the Black Experience, compiled by the Burke County Cultural Arts Coalition, 1979

Black and White: The Story of Harriet Harshaw and 'Squire' James Alfred Dula by Leslie D. McKesson, Ed. D. recent appointee to the African-American Heritage Commission.

My Story: This Is How It Was by Helen Phillips Hall, the first African-American associate superintendent of Caldwell County Schools

Glimpses of Fonta Flora, by sisters Helen Norman and Patricia Page, who grew up near Lake James

Giving Back: A Tribute to Generations of African American Philanthropists by Valaida Fullwood, a writer and project consultant who grew up in Morganton

Race, Paternalism, and Protest in Morganton, North Carolina by Michael Ervin

The West Concord Mothers: Coming into the light

Written by Dr. Leslie McKesson, member of the Morganton Writers Group

Published in The News Herald, April 17, 2022

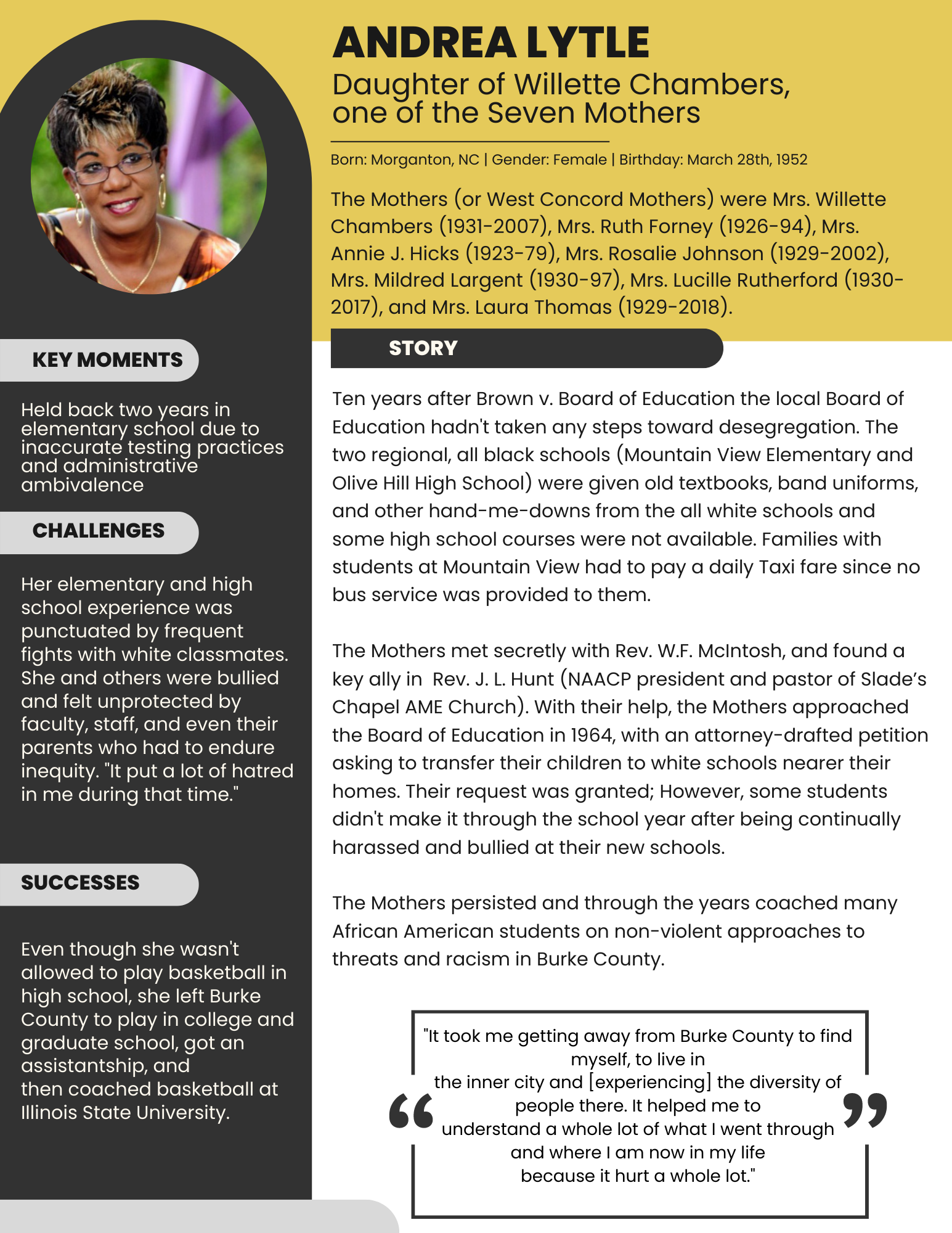

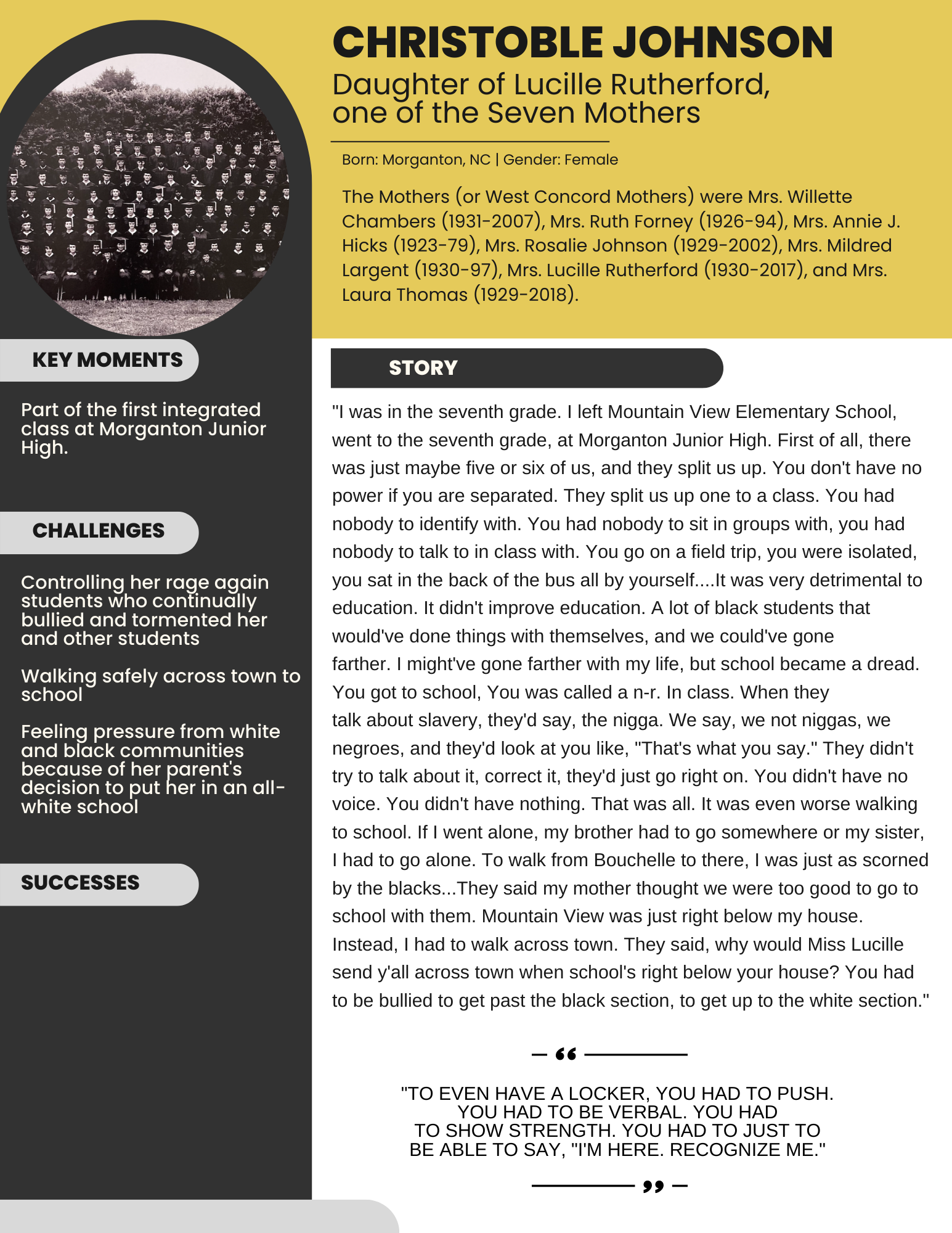

The West Concord Mothers, also known as the Seven Mothers and the West Concord Seven, could be considered hidden figures behind the local desegregation movement from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Little has been written about their fascinating history, but a more complete story of “The Mothers” and their work is coming forward through community members who want to reflect upon and share their experiences from that time. Some knew The Mothers as their own parents. All knew them as role models, guides and mentors.

The Mothers were Mrs. Willette Chambers (1931-2007), Mrs. Ruth Forney (1926-94), Mrs. Annie J. Hicks (1923-79), Mrs. Rosalie Johnson (1929-2002), Mrs. Mildred Largent (1930-97), Mrs. Lucille Rutherford (1930-2017), and Mrs. Laura Thomas (1929-2018). A March 6, 2005, News Herald article indicated that several of them lived in Morganton’s historic Jonesboro district near West Concord Street, giving them the name “West Concord Mothers.”

I learned about The Mothers in 2015 during a Black History Month presentation at New Day Christian Church. The program was spearheaded by Morganton native Gary Harbison, who was inspired by his memories of the Civil Rights era as a youth. Harbison wanted to recognize The Mothers for the strategic role they played in advancing the rights of Morganton’s Black citizens.

Mostly domestic workers, The Mothers led the local school desegregation effort believing that if men led the work, they would be more subject to threats and job loss. According to Artie McKesson Logan, a student who was mentored by The Mothers, the men worked invisibly to guarantee the physical safety of the youngsters.

The Mothers’ goal was to provide an equal education for their children. In 1964, having grown frustrated with the local board of education’s lack of progress toward desegregation, they started meeting secretly at the home of local educator and pastor of Green Street Presbyterian Church, the Rev. W.F. McIntosh.

Andrea Chambers Lytle, daughter of Mother Willette Chambers, remembers that the group met after dark to minimize the risk of being observed by people who opposed their work.

The children in question attended two of the county’s Black schools, Mountain View Elementary and Olive Hill High School. The textbooks, band uniforms, and other supplies they used were handed down from white schools, and certain courses they wanted to take at the high school level were not offered at Olive Hill. McIntosh advised The Mothers, coached them on process and approach, and helped them strategize.

Another key advisor was NAACP president and pastor of Slade’s Chapel AME Church, the Rev. J. L. Hunt. Some of The Mothers were members of his congregation and the NAACP, and he availed the church to them for meetings.

A Feb. 5, 2012, News Herald article indicated that The Mothers approached the board of education in 1964 with an attorney-drafted petition asking to transfer their children to white schools nearer their homes. Their request was granted.

The Mothers walked their children to Forest Hill and Central schools daily as the men surveilled from nearby, but out of sight. After being harassed and unhappy at their new schools, the students returned to Mountain View before the academic year ended. Lytle spoke of particularly traumatic racial experiences while attending Central.

Media coverage was sparse. In his bachelors’ thesis titled, “A Powder Keg That Could Easily Explode: Race, Paternalism, and Protest in Morganton, North Carolina,” Michael Ervin partly attributed this seeming silence to municipal and media leaders’ efforts to maintain a moderate-to-progressive community image by minimizing reports of racial tensions.

Ervin believes, however, that leaders’ desire to keep local conflict out of the news gave activists like The Mothers leverage to press for their goals. The Mothers also knew that publicizing their work would jeopardize their livelihood and personal safety, so media silence was advantageous.

Logan said The Mothers prepared students for a new and potentially hostile environment by training them in non-violent approaches. They instructed boys to wear a tie to school every day, told all students to keep their grades up, to always be on their guard and also on their best behavior, and taught them how to respond to heckling and threats.

Lytle experienced the tensions between the unflinching expectation of exemplary behavior in the face of racism and the fact that she was the daughter of one of The Mothers. She had frequent fights with white classmates because she was bullied and felt unprotected by faculty and staff.

The Mothers had previously coached youth to peacefully protest their exclusion from the Collett Street Recreation Center in 1963. Over a period of several weeks, facility administrators repeatedly denied Black children access to the gym, saying that the dirt on their shoes would damage the new floors, while allowing white children in the gym in their street shoes.

Advised by The Mothers, Logan said “[Students] purchased brand new tennis shoes” bringing them to the gym tied across their shoulders “so that they wouldn’t say that we were bringing dirt and sand and things in there.” Collett Street Rec opened the gym to Black children in 1964.

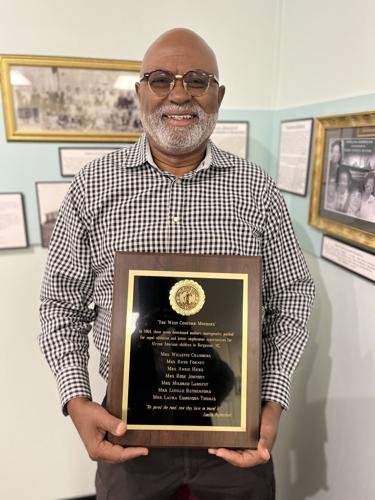

The Mothers’ work impacted desegregation through the 1970s, when Mother Lucille Rutherford said they helped Black adults get factory jobs previously reserved for whites. Decades later, she attended the recognition ceremony at New Day Christian Church, where she was presented with a plaque recognizing The Mothers.

The plaque was placed on display at the History Museum of Burke County, where it is part of the permanent oral history exhibit called, “Children of the Struggle – the Desegregation of Burke County, NC Public Schools.”

The young people who pioneered desegregation under the tutelage of The West Concord Mothers have varied and complex stories to tell. Some speak of easier transitions into integration, while others tell of the trauma they still carry.